Game Changers for launching products successfully

“Knowledge isn’t power until it is applied.” — Dale Carnegie

This year, no topic has influenced me as much as Lean UX. At the beginning of the year I decided to gradually put my theoretical knowledge into daily practice. As the year is slowly coming to an end, I would like to share my thoughts, findings and experiences with you.

First of all: It’s never too late to correct the course!

I often had to listen to sentences like “It’s too late” or “We should have done that at the beginning.” In the context of digital products and lean manufacturing methods, these statements — for me — lose more and more of their correctness.

Once, we had a project that struggled. We tried to understand why. We did retrospectives, checked our toolchain, etc. and did not come to any result. Then, we changed our focus and we identified that many of the problems we had were not caused by WHAT we were doing, but by HOW we were doing it.

Shortly after that, we had to decide: Should we take a different path (like alternative approaches and methods)? Or do we stay on the track defined at the beginning — knowing that it is getting bumpier and bumpier?

The fact that we were already in the process made the decision not easier. And even if it was bumpy, we had already invested power (time and money) and generated some output. It was like we were feeling the Concord Effect.

It’s about doing it together

In most cases, you create products, not for yourself and not by yourself. You will need the trust, commitment, and support of other people (and departments). So Share your vision and thoughts: no long e‑mails, big meetings, Jira-tickets, or Excel sheets. Just go to them. Have a chat and integrate them as much as it is possible. Show them how valuable they are. You will see, most people are willing to participate. Get them on board.

Product teams are most effective if they work together as closely as possible. Seize some Space ( or a room), hang the walls full of the things you’ve made and you’re proud of. Talk about it with everyone who passes by.

Remote, however, should remain the exception (like if you want to do Home-Office or something like that), but not the rule.

In the end it is the people who create products — not methods, processes or tool.

Assumptions are welcome

If you want to avoid endless discussions and design-by-committee rounds, gather just enough informations to form a hypothesis, then transfer it into an experiment and start learning — through real market feedback.

As explained in the Book Outcomes over Output (by Joshua Seiden), a basic hypothesis has two parts:

- What we believe

- The evidence we‘re seeking to know if we‘re right or wrong

Frame the problem in such a way, that it almost begs for the next step to be an experiment or research project, to see if your hypothesis is right or wrong.

The Lean UX Canvas (by Jeff Gothelf) is an excellent tool for translating business problems into assumptions, hypotheses and experiments.

Stay small and lea®n

There is a common (sequential, linear) approach for developing software and it works (more or less) like this:

Three or more months of gathering requirements to identify the whole product scope.

Three more months of concept creation followed by another three months of User Interface and Visual Design.

Six more months for development and two for bug-fixing testing.

Finally: the Go-Live. Sounds like a no-brainer, right? Unfortunately only in theory.

Now, let us put in some reality to make it more practical:

Add a bunch of discussions about changing or misleading requirements, personal taste, rejected approvals, and never-ending feedback-cycles. Then multiply it by the sustained pressure affected by reaching a deadline (and a scope) that was determined and estimated at a point when most things are uncertain: at the beginning.

The Result: You probably will not meet the deadline, not reach the scope and the budget will double. And — even if you launch a usable And working product (after 1,5 years) — you have to fear that nobody will use it.

Pure pain!

But how to deal with such problems?

The answer: Start small and learn.

For example: If your most significant fear (risk) is to create something that — in the end — nobody wants, it should be your highest priority to verify if there is a potential user group or market for your product or Service before you start building it.

How? Imagine a banal 3‑minute video on a landing page demonstrating the product as it is meant to work. Target it to a community of early adopters and learn. That is — more or less — the way DropBox started.

There is an alternative to traditional personas

Personas are user models showing the characteristics of persons in a target group. They can, for example, help a development team to put themselves in the position of potential users to better understand and represent their goals, behaviors, preferences and expectations throughout the design process.

Sometimes, personas are viewed as some panaceas.

There is a traditional way of creating personas: at first you have to dive deeply into a phase of user and market research.

Next, you will be doing a lot of surveys. Eventually, this might end up in loops of evaluation to prove the data’s accuracy — and sometimes about the structure and design also.

Lean (or prototype) personas are slightly different.

Lean personas are created fast. The deeper you dive into your target groups by doing small interviews and testings — during the design process — the clearer the persona becomes. And instead of advanced artifacts designed to be declared as finished (at some point), lean personas are seen as living objects using a simple and flexible framework.

Sketching (and prototyping) is king

Sketches are helpful when it comes to sharing ideas. Many people assume that they are not good at sketching things. And that’s ok. Because that is not the point. You don’t have to be good. As long as you’re able to draw lines, circles and squares, you’re in!

And it is not about beauty! It is about bringing your thoughts to paper, so you’re able to share them. If you still feel that you cannot sketch, try it out.

And if you want to improve your sketching skills, there are numerous books, Youtube videos and articles waiting for you.

Prototyping gives you the possibility to make ideas tangible. It can be a tool that enables stakeholders to make reliable decisions — quickly and early. And you can use it to validate assumptions in qualitative interviews.

Kinds of prototypes

- Sketch or Paper Prototype:

This is the most abstract form of prototyping, in the form of hand-drawn sketches or written/painted storyboards — and sometimes napkins too ;). - Bastler Prototype:

It isn’t pretty and made without claim to Design Guidelines or correctness of the content. - Craft Prototype:

Normally better looking and working than a Bastler-Prototype, this one contains more details (like business logic, design requirements, or content). - Preseries Prototype:

A preseries prototype is almost like the final manufactured product. In shape, size, function and logic. It’s the last step before getting into production. It’s also a functional blueprint for the development handoff — Instead of manually measured screens and endless concept descriptions.

Validation variants

- Self-validation:

As a Designer, we do this method in our daily work. By using different prototyping- and wireframing software (like Flinto, Principle, Adobe XD, Axure, etc.), paper-prototyping, video prototyping, modeling, hand drew sketches and HTML-snippets — Also to ensure validation for our selves. - User-validation:

In the first case, our Concept-Solutions are theses. So we have to validate these hypotheses against real user and context and to gather information about background and needs. To do this, we use Methods like User-Testing and Interviews. - Business-validation:

If we talk about KPIs and Business-Logic, we are also able to check early the achievement of them, collect stakeholder feedback and enable clients to make a business decision even before launching the product earlier on. It is also an excellent basis for discussion. - Technical-validation:

To avoid nasty surprises in production, we are able to clarify technical questions or find technical solutions early.

Create a shared understanding!

I have rarely seen such power in something, as I see it in shared understanding.

Many development teams have Jira, Excel lists or similar tools to keep track of the backlog. Often, one person is responsible for the backlog, writing Epics. Someone else has to break these Epics down and has to add the details and acceptance criteria. Still, other people are assigned to estimate and develop this story, based only on the User story description.

One major issue lays in a lack of communication. As team members will most likely have different interpretations and expectations, a shared understanding should be established right from the start of the project.

User Story Mapping

With User Story Mapping, you can create a backlog together that makes dependencies, risks (spikes) visible and extended by sketches and information. It is not a vertical list on a screen. It is a flexible matrix on the wall.

The most important thing: do this together with all the representatives of the different practices and crafts. Create a shared picture of what to develop in the next release and to identify what is needed to ensure it.

You can release running software earlier

“The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.” — Albert Einstein

In the beginning, it was hard for me to understand how to release working software on a weekly or daily basis. Moritz, a colleague of mine, then told me his experience of working in a fully agile company:

„The team came together for an hour in the morning. They took the story, ideated together on a flip-chart (to create a shared understanding) and implemented it until the evening. It is possible, when you break down your stories until you can develop them in one day (or less).“

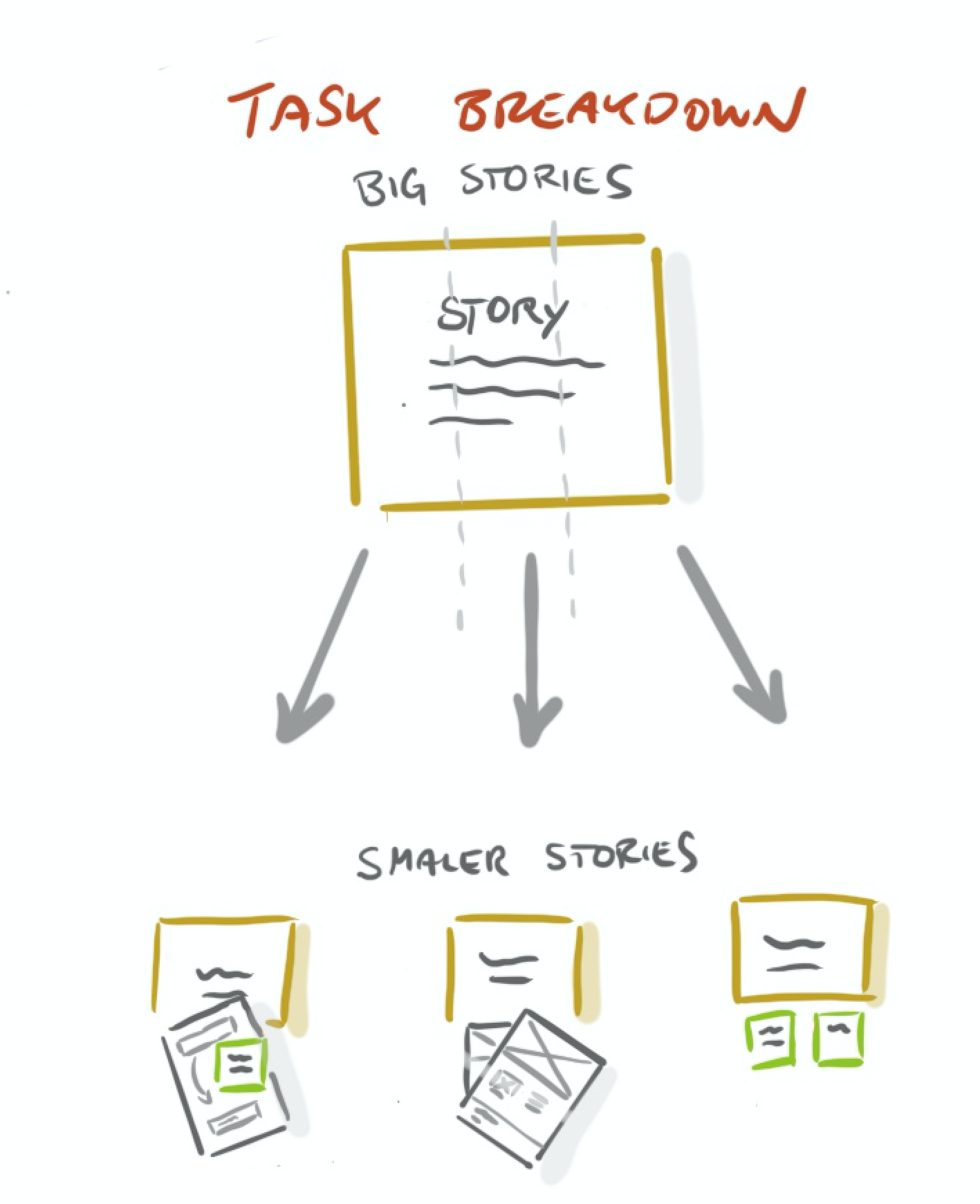

The aim is to break down bigger stories so that the real scope is made clear. Small stories are better to imagine. For example, if you have the story I want to search for files, what is really behind it in detail becomes apparent first, when you start to talk about it. So break them down!

Break down your stories (and tasks) — to ensure smaller badge sizes

The sentence I hear most often by doing breakdowns is: “That’s more complex than I would have thought.” Another one? “Now, we can see which dependencies we have.”

I’ve heard several different names for story sizes like Story points. Besides, teams also like to use T‑shirt sizes (S, M, L) or animals (mouse, dog, cow, elephant). In this case, the biggest unit (L or elephant) indicates a story that is too big to be estimated. So you have to break it down until you can estimate it.

I prefer a slightly different model. Instead of estimating a story and giving it points or names, we try to break down every story until it is small enough to be realized in one day (or less).

We also use story mapping for this. We (the feature team) transfer stories from the flexible backlog and detail them. We enrich the smaller stories with information, ideas, sketches, unknowns, alternatives and risks.

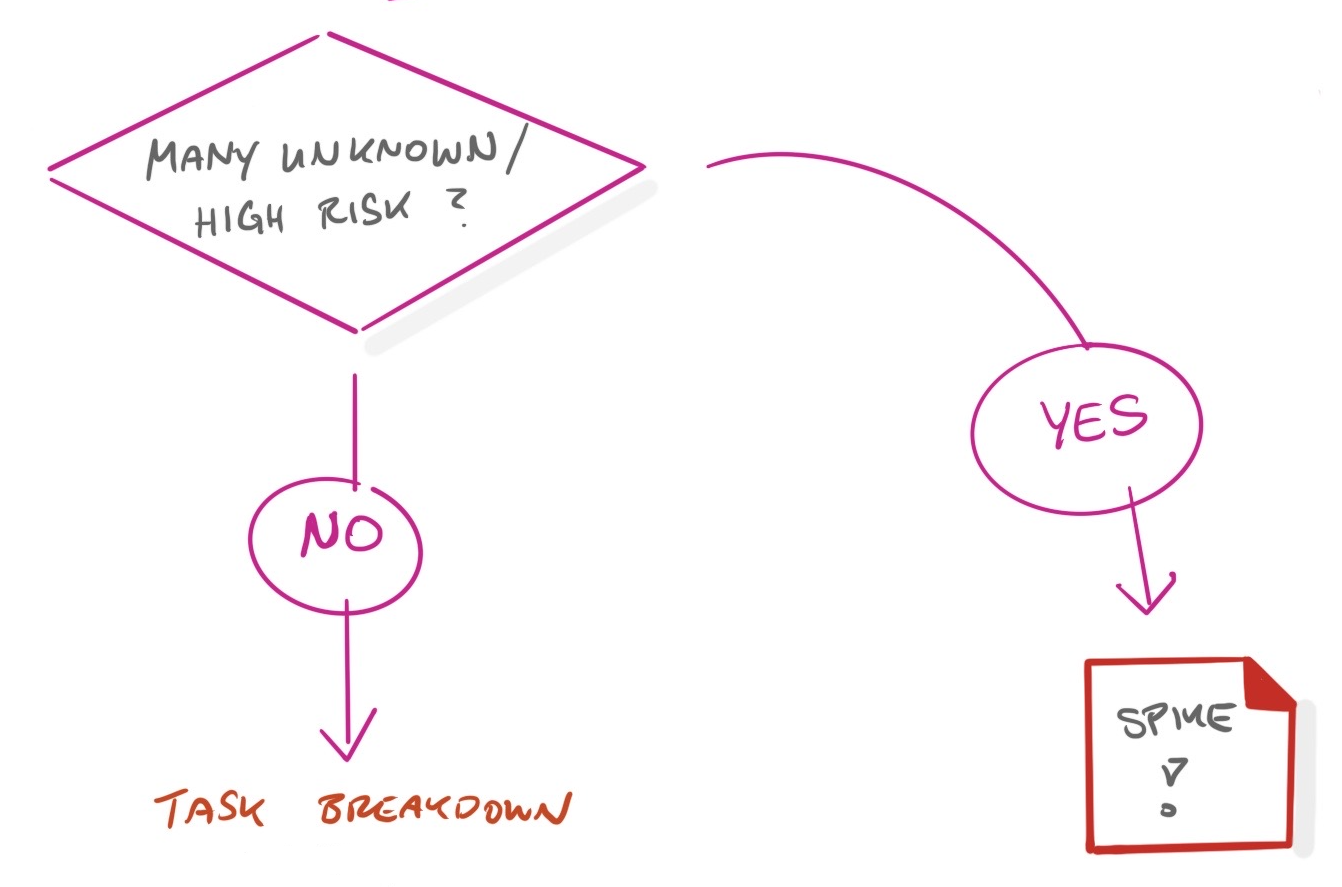

Risks are a part of the game

We live in a world full of uncertainties. And because of that, it’s helpful to identify risks already during the release planning. If you recognize a risk, don’t ignore it. Deal with it! Make it visible!

An example: On one of our last workshops, we assumed that the theme Registration & Login is a No-Brainer. Done a thousand times already, so it’s probably easy to break the item down into smaller stories. Then, during the release planning session, we identified unclear dependencies to the interface of the 3rd party provider. None of us could evaluate it. And we were unable to assess the topic in terms of scope or time -> A risk of not reaching the release date. So we declared it as a Spike (a theme or a story with risks/unknowns that have to be validated quickly).

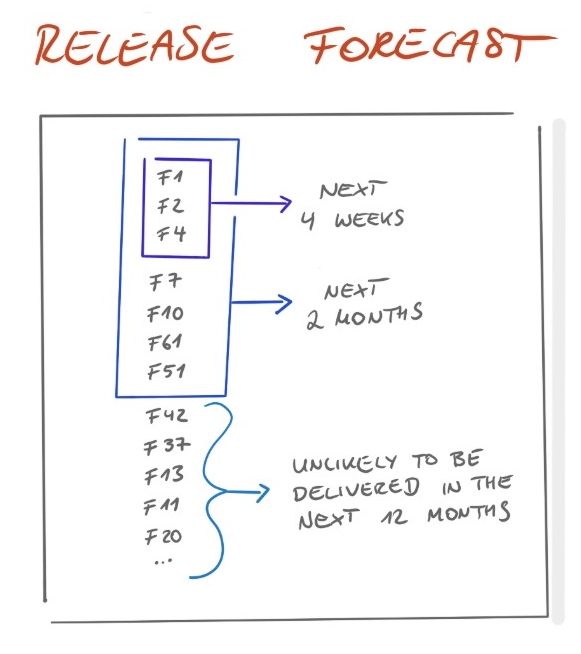

Use a release forecast instead of Gantt Charts and Deadlines

Estimating long-term projects at the start is a pain. Today we are aware of the fact that it is not possible to predict the future and to identify all risks, dependencies, and the full scope at the beginning, on the one hand and being innovative and flexible at the same time on the other hand.

Although there will be someone in most projects, who needs an assessment of what is ready, in progress or planned next, many find this information annoying. And if you don’t see any importance for yourself, some stakeholders and project sponsors might will need this information to create reports and status to their superiors.

In his book #NoEstimates, Vasco Duarte describes a tool called Release (or backlog) Forecast. You use can the Story-Map (Flexible Backlog) as the template for delivering a release forecast, for stakeholder, showing:

- What will we provide in the next four weeks (sprint backlog)?

- What (most likely) will we deliver in the next two months (Release Backlog)?

- And what will most likely be not delivered in the next two months (Product Backlog)?

See this tweet from Vasco (based on Chaos Report, Casper Jones ‘Journal of Defense Software Engineering’, McKinsey & Uni ‘Oxfords Study of Large Scale IT Projects’ from 2012 and his Data):

“We are perfectly able to Estimate the future.

We are so good that: 60% time overruns is the average; 66% of large IT Defense projects are late and/over budget; 17% of large projects go so bad they threaten the survival of the company!

Yeah, we are ABLE to estimate #NoEstimates”

— Vasco Duarte

Vascos’ book is filled with statistics and examples explaining why the traditional way of estimating is not the best. Mostly it is not about the What but about the How. So, if you want to create products or services that matter, be aware that you have to be flexible to changes — Because the world turns.

Get out of the Building

When it comes to conducting qualitative interviews to get insights, GOOB (Get Out Of The Building) is probably the most effective method you can choose.

Go out and go where the people themselves are sitting. Spend a day with the people who use the product or service, or also talk to those whose job depends on it.

Enriched by parallel surveys and quantitative research, you get a better picture of the usage of the product or service.

It also serves you to validate the personas, which — initially still based on assumptions — provide a sharper and more accurate picture of the user groups.

Sometimes it is frustrating

Even though I am still at the very beginning of my lean-ux-journey, I try to integrate lean thinking — step-by-step — into my daily activities. Sometimes more, sometimes less successful. And sometimes it is frustrating as well. For example, when I identify waste in my own actions — usually afterward.

Now, I am very curious to see where the journey will lead me, but also us as a team In 2020.

Special thanks to Maeve O’Flynn, Christian Kilian, Fabian Möller, Fabian Gaber, and Jan Sagemüller for their help, feedback and patience (with me).

Thx for reading 🙂

Feedback on this article is highly appreciated.

This article is also available on Medium